International Heritage Centre blog

Adjutant William Avery and the 1914 Bombardment of Hartlepool

Adjutant William Avery and the 1914 Bombardment of Hartlepool

We usually think of attacks on the civilian population of Britain as a feature of the Second World War - epitomised by The London Blitz - but during the Great War, Britain was bombed by both aeroplanes and airships. On 16 December 1914, less than five months after the outbreak of the First World War, the towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, in the north-east of England, were attacked from the sea.

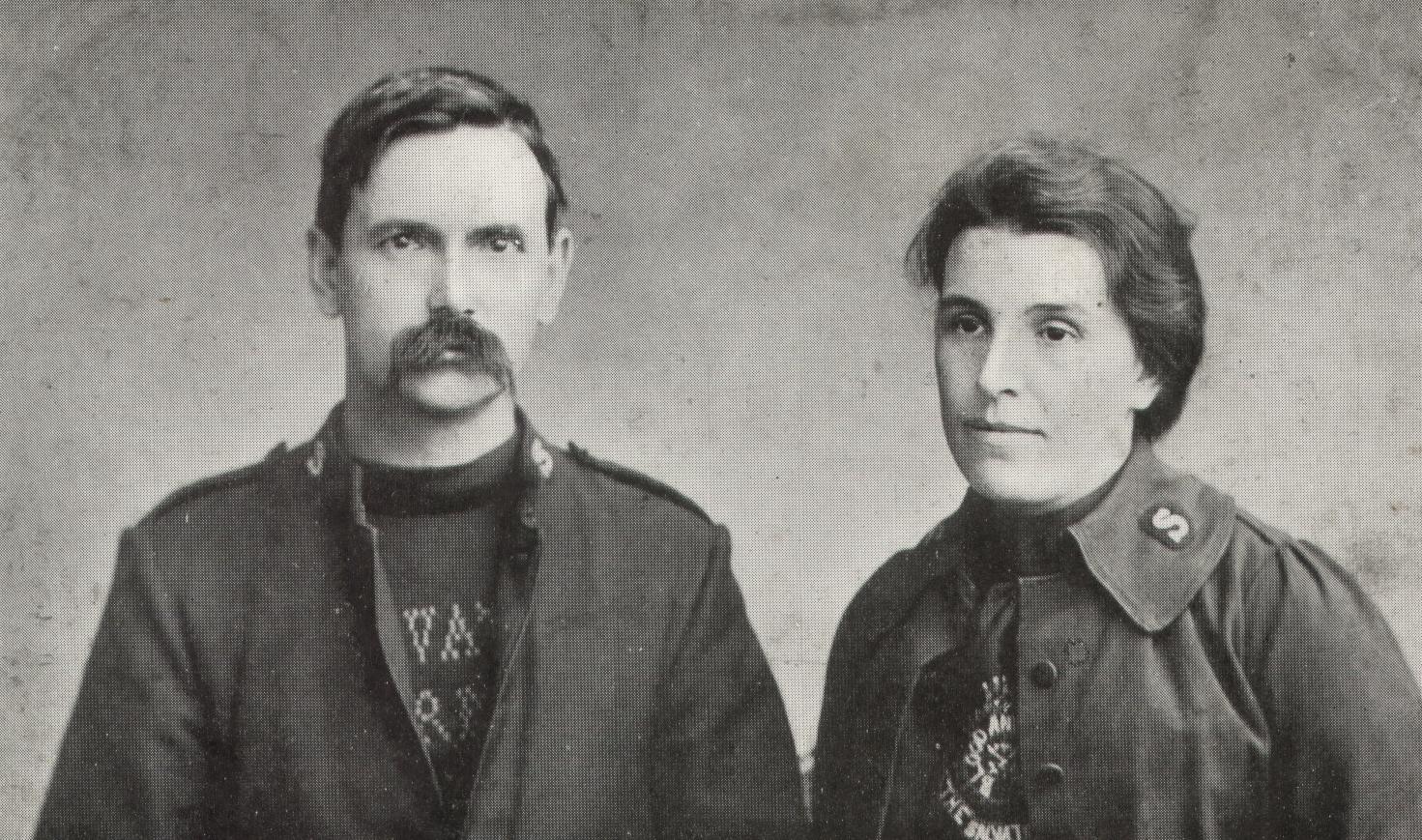

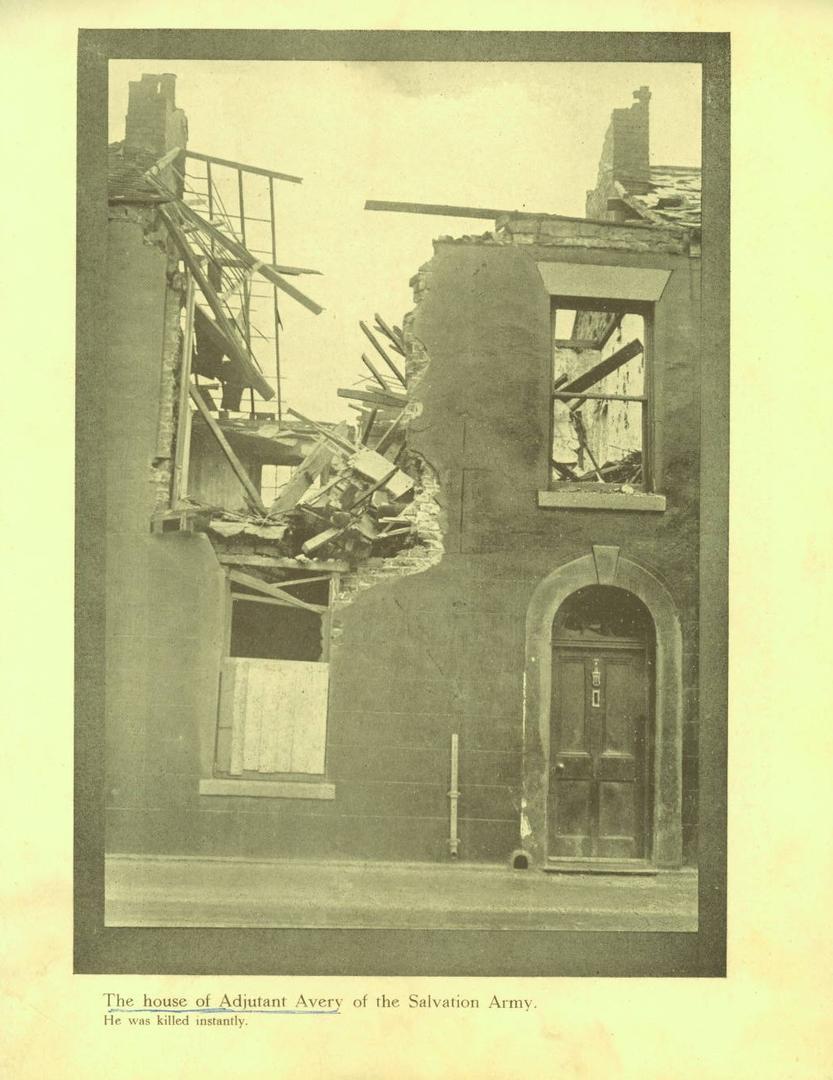

At No.7 Victoria Place, Hartlepool, Salvation Army officer Adjutant William Avery was killed instantly when a shell struck the house. He had been bringing his family downstairs and was coming down himself when the German naval shell exploded. William and Julia Avery, the officers in charge of West Hartlepool Citadel, had served together for twenty years, in various Salvation Army churches in Ireland and the north of England.

So why had Germany started targeting civilians in this way? Firstly, the Germans needed to boost morale in their own navy after a crushing defeat against the British in the Battle of the Falklands the previous week. They also wanted to damage the morale of the British public, in the hope that they would clamour for more troops to be kept for homeland defence and so away from the continent. The German fleet wanted to draw out small sections of the, much bigger, British fleet, which it could then destroy piecemeal.

Working from a captured German code book, the British were aware that a German force would shortly be leaving port to attack British coastal towns, but did not know which ports would be targeted or how large the German force would be. One intercepted message mentioned places as widely separated as Harwich and the Humber, making it very difficult to co-ordinate a response. Because of this the Royal Navy planned to let the raids go ahead, intercepting the attacking ships as they withdrew.

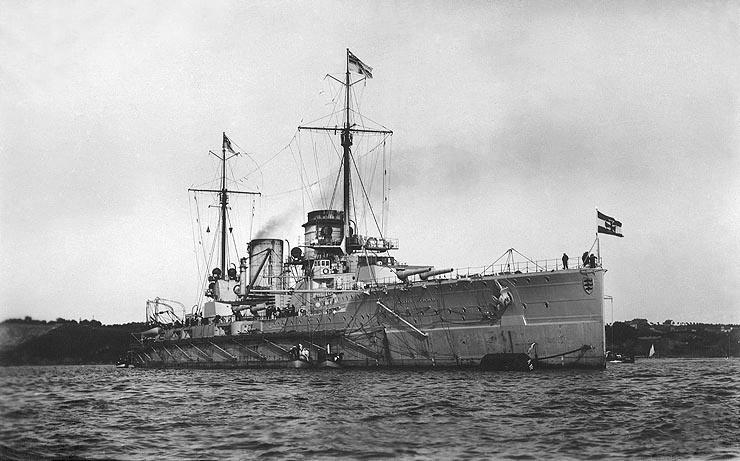

A sizeable German force headed out into the North Sea at 3.00am on Tuesday 15 December, the night before a new moon, and what little moonlight there was hidden by gathering cloud. Soon, many of the smaller escort vessels were forced to return to port because of the deteriorating weather. When the remaining ships split up, the battlecruisers Blücher and Seydlitz (the 25,000-ton flagship of this small force) and the smaller armoured cruiser Moltke, headed for Hartlepool, the remaining ships heading for Scarborough and Whitby.

Because British naval forces in the area had not been alerted, just four small (none more than 700 tons) destroyers were on patrol, and they had to run from the more powerful German force after two were damaged. A pair of light cruisers (about 3,000 tons) in Hartlepool harbour when the attack took place fared little better, with one being badly damaged.

Several sources repeat claims that the three ships were flying British flags as they approached Hartlepool, changing them over only when they were ready to fire. It seems more likely that they were able to get so close to the defences without being identified because of the poor visibility at the time, rather than any subterfuge.

07:46 Shore batteries received word that ‘large ships’ had been sighted. When they became visible through the mist, attempts were made to establish contact, but no reply was received.

At 8.06 on the morning of Thursday 16 December, the German ships appeared suddenly out of the fog and started firing at the patrolling destroyers, damaging some and driving off all of them. They also engaged the coastal defence guns.

08:10 Bombardment of the town began.

By 8:25 the ships had approached to within four thousand yards of the shore. Despite being severely outgunned, and taking casualties from German fire, the shore batteries successfully engaged the enemy ships. Blücher was hit six times and Seydlitz sustained three hits from the British guns, while Moltke took just one. This fire from the coastal batteries did only minor damage to the warships, but was sufficient to force Blücher to move further out from the shore.

08:50 The German ships turned away and headed back out into the North Sea.

The first shells fired had landed beside the battery on the Headland and killed four soldiers outright, ‘the first British soldier[s] to die from enemy action on British soil since the battle of Culloden in 1746’.

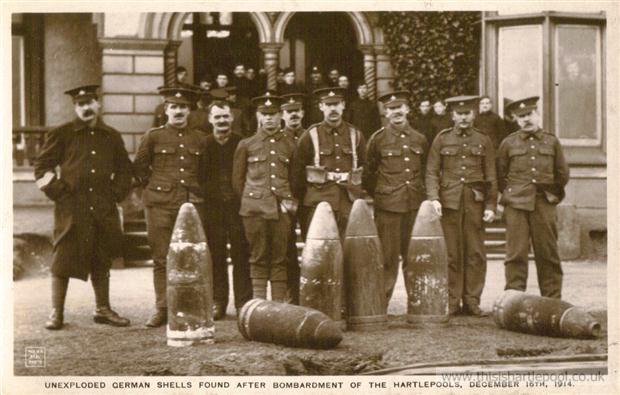

Of the estimated 1,150 shells fired at Hartlepool during the attack, many failed to explode. The 11‑inch shells pictured above were fired from the largest guns carried by the two battlecruisers. Weighing well in excess of a quarter-of-a-ton, these shells were capable of demolishing a house, even if they didn’t explode! But they were not necessarily faulty. Designed for use against armoured warships, they were meant to penetrate the hull, exploding inside a split second later – the impact of hitting a brick building was probably not enough to set off the fuse.

Despite large numbers of people attempting to flee the town, 114 civilians were killed and a further 443 injured; 37 of the dead were children. In addition, seven of the soldiers manning the coastal batteries were killed, with 14 injured. Scarborough suffered 18 dead and Whitby two.

By 09:45 all German ships had reassembled, and began to head back to their bases. In response, the Royal Navy had dispatched a sizeable force to ambush them as they returned from the raid.

At 11:25, a British cruiser sighted enemy ships, but the bad weather hampered efforts to maintain contact. Additional ships were dispatched to assist the first, but confusion in signalling resulted in all the vessels breaking off the pursuit.

12:30 Another attempt to engage the enemy was thwarted by another signals problem, and all German forces returned safely to their home ports. The ‘Hartlepool’ ships lost eight sailors killed and 12 wounded.

The Admiralty’s response of the raids was, at best, ill-judged; "…that the bombardments might cause some loss of life among the civil population and some damage to private property… was much to be regretted, but they must not in any circumstances be allowed to modify the general naval policy that was being pursued.” This may have been driven by the classic military dilemma – whether to be relatively weak everywhere or strong in just a few places – but it did little to inspire public confidence.

The public’s response to the raids was not straightforward. On the one hand there was an outcry over what was seen as the Royal Navy’s incompetence in letting the Germans strike these mainland towns and escape virtually unharmed.

While on the other, the anger against the Germans at such an atrocity caused thousands of men to queue at recruiting offices wanting to ‘do their bit’ and ‘avenge the deaths of the innocents’. The government produced posters such as the one above urging the population to ‘Remember Scarborough!’ The German’s attempt to influence British morale had misfired disastrously.

But why were these towns attacked? A detailed study of the English coast by German submarines would have shown that the defences of these towns were weak. Only Hartlepool possessed coastal guns, and even here there were just three, relatively small, artillery pieces.

Why ‘Remember Scarborough’, when Hartlepool had suffered by far the worst casualties? It may have been because Scarborough was known throughout the country as a seaside resort, while Hartlepool had extensive civilian shipyards and engine factories, and may have been considered to be a ‘legitimate’ target.

Postscript

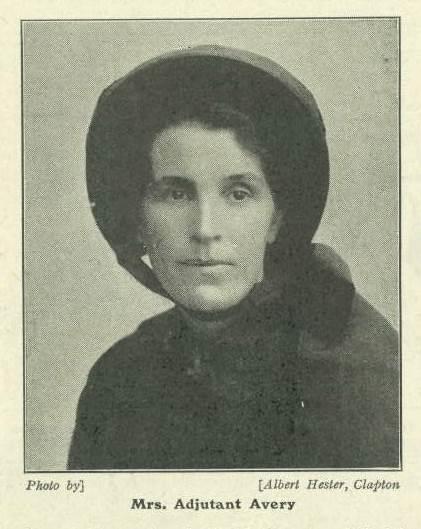

In October 1916 we find Mrs Adjutant Avery on the staff of The Salvation Army’s Clapton maternity home in London, where she says ‘I am so much happier working’, describing her work with ‘…the dear wee babies’. We also learn that ‘Her three elder children are working at Headquarters, while the two younger ones are still at school’, and the family lives just a few miles away in Walthamstow.

Kevin

December 2018

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

Chinese Christian Posters

We are delighted to have been able to contribute to a wonderful new online resource from the Center for Global Christianity and Mission, Boston...

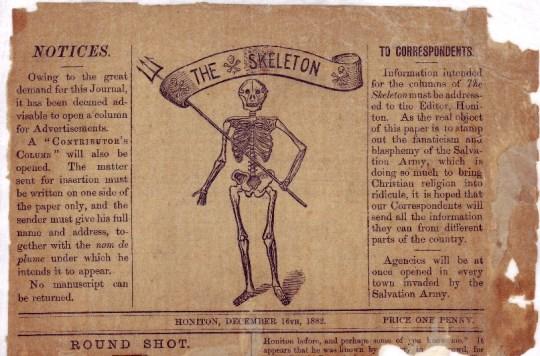

Blood, Fire, Skulls & Crossbones: A Battle Between Two Armies

In the 1800s Salvationists took to the streets with blood and fire in their hearts, but the reactions that they received were a little fierier than expected...

‘Drunkards’ Raids’ & ‘Boozers’ Days’: The Salvation Army’s ‘war on drink’

In the 1890s The Salvation Army described itself as “a universal Anti-Drink Army” and this blog looks at two examples of this war on drink...

Guest blog: Black History Month

In our first ever guest blog, William Booth College librarian Winette Field explores the history of black Salvationists, evangelists and missionaries in the UK...