International Heritage Centre blog

'Receive, reform, regenerate, restore': Beggars' Town, Shanghai

'Receive, reform, regenerate, restore': Beggars' Town, Shanghai

As 2016 is the centenary of the beginning of Salvation Army work in China, we have been looking more closely at the records we hold from China. These records are among the most substantial that we have from any individual country outside the UK. One of the most intriguing files we hold comprises a series of press photographs from the 1940s showing a settlement in Shanghai known as Beggars' Town. Using details written on the reverse of the photographs, it has been possible to find articles about the camp in contemporary Salvation Army periodicals, such as All the World and The Crusader. All the World is a quarterly magazine about Salvation Army work around the world and which ran a photo-feature on Beggars’ Town in April 1942. The Crusader was an English language periodical published by The Salvation Army in Beijing, which carried regular articles on the development of the camp.

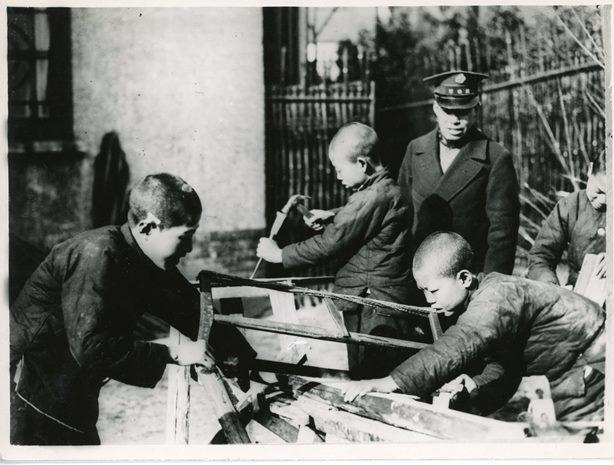

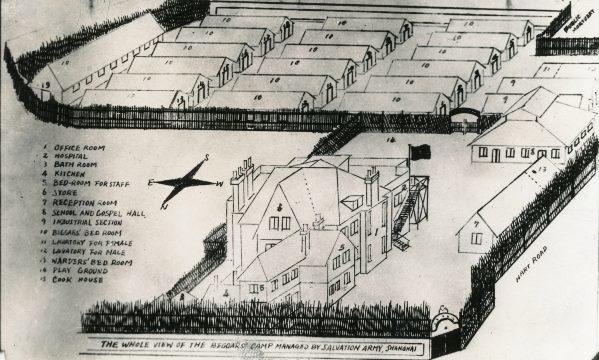

Beggars’ Town (also called ‘Beggars’ Camp’, ‘Beggars’ Colony’ and ‘Beggars’ Home’) opened on 1 January 1941, situated on a former drill ground used by the US Marines, and comprising 26 houses with accommodation for 1,500 people along with a Gospel Hall and a hospital. This settlement, set up with the support of the Shanghai Rotary Club and the Municipal Council, was a response to the large number of homeless people in the city, many of them refugees. The Chinese Civil War had begun in 1927 and the Japanese invasion in 1937 only exacerbated the flow of people away from violence and banditry in the countryside towards the relative safety of the cities. Shanghai itself was occupied by the Japanese in November 1937. The express aim of the camp was ‘to receive, reform, regenerate, and restore to society’ the homeless population of Shanghai. It included a school for adults and children (where the Chinese phonetic script was taught) and workshops for handicrafts such as weaving, basket making, carpentry and tailoring. All the work of the camp was carried on by the residents themselves, including a “Camp police to assist in maintaining good order.”

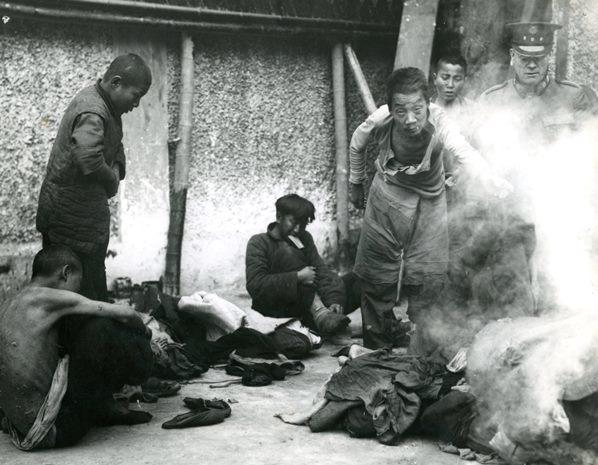

Men, women and children were gathered up by the police and brought to the Camp in police vans. New arrivals were photographed, fingerprinted and classified into groups according to professional abilities and their province of origin. Their clothes (described in All the World as ‘verminous, germ-laden rags’) were burned to prevent disease entering the Camp and cotton-padded clothing provided.

The original intention of the Municipal Council had been to make confinement in the camp compulsory, but this was abandoned in light of the good behaviour of the first groups of ‘beggars’ admitted to the Camp. It was then decided that, due to the success of these first groups, admission to the camp would prioritise drug addicts and people with severe illnesses and physical disabilities.

The residents were to leave as soon as they were able to earn a living and, by August 1941 it was reported that “the camp has now actually become, as originally intended, a ‘Clearing House.’ Some stay at the camp for a few days and are then sent home or back to their relations, whilst others stay for a prolonged period before being sent to work or ‘cleared’ in some other way.” In November 1941 The Crusader reported that, after operating since 1 January 1941 it had been decided to close the Shanghai Beggar Camp at the end of March 1942 and to establish a Beggar ‘City’ on Chinese territory. A full report was to be published in a future issue. However the ongoing conflicts in mainland China increasingly curtailed the activities of The Salvation Army and The Crusader ceased publication after 1941.

Beggars' Town has been discussed in some detail in Janet Chen’s book Guilty of Indigence: The Urban Poor in China, 1900-1953 (Princeton, 2012).

Steven

September 2016

Read other blogs from the Heritage Centre

‘…behind the barbed wires’: internment on the Isle of Man

Explore the letters of officers Lieutenant-Colonel Walter and Esther Busse, interned as 'Enemy Aliens' for over five years during the Second World War...

First World War Babies

Between 1897 and 1972, women seeking admission to Salvation Army homes in the United Kingdom were interviewed at The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work (WSW) headquarters in London...

A contextual complexity: the Special Efforts Department

Exploring the work of a department for which no administrative papers have survived...

A lesson in judging books by their covers

Looking at the above picture you’d be forgiven for thinking that the volume in the centre would be easy to describe in our archive catalogue...