International Heritage Centre blog

Out of love and small earnings

Out of love and small earnings

In one of my previous blog posts, ‘Inside affairs’: cataloguing the Henry Edmonds papers, I described how the papers had helped me to piece together the story behind an unusual cabinet card in our collection, and that story involved the legacy of the wealthy benefactor Elizabeth Orr Bell of Harviestoun Castle.

Uncovering Mrs Bell’s story got me interested in finding out more about other women whose contributions bolstered and expanded the work of The Salvation Army in its early decades. Following on from my second blog on another donor, Olive Christian Malvery Mackirdy, Virtuous Bodies and Women Who Miss Trains, this post is the third in this mini-series.

As part of The Salvation Army’s annual anniversary celebrations at the Crystal Palace in July 1891, a tea was held for ‘old girls’ of the rescue homes. These ‘old girls’ were women who had passed through The Salvation Army’s residential ‘rescue’ programme and had subsequently held down a position in domestic service. Florence Booth, the leader of the Rescue Work, used the occasion to make an important announcement. She was launching a new scheme which aimed to raise funds not only to open another rescue home but to provide a steady income for it for many years to come.

The home she proposed was a refuge for mothers with young babies. This type of home, she argued, called for a special funding scheme because new mothers would not be in a position to contribute to their upkeep by producing needlework for sale in the way the women in other Salvation Army rescue homes were expected to do. However, the most novel feature of the proposal was that the home would not be funded by donations from wealthy benefactors but by the ‘old girls’ themselves.

Bearing in mind that her audience was made up of women who, only recently, had been in such precarious circumstances that they had sought assistance from The Salvation Army to escape the dangers of poverty and social exclusion, and who, even as she spoke, were in low paid and insecure employment, this could seem quite a surprising plan. Might they not have been better advised to save what little they could spare from their meagre earnings to provide security for themselves in the future?

Publicity for the scheme encouraged a more community-minded approach, arguing that ‘little savings … might otherwise be spent thoughtlessly’, so better that they go to help others ‘whom you have known in darker days of sin, [and] who shall bless you in all eternity as the means of their temporal rescue and everlasting salvation’. Careful calculations had been made:

‘of the five thousand girls who had been dealt with through the Rescue Headquarters, at least two thousand could easily contribute one penny per week towards the support of a new Rescue Home, thus forming an annual income of about between £400 and £500 a year, which would support a Home accommodating about twenty-five girls.’

The plan sounded straightforward and the immediate reception was promising: ‘really and truly […] the fund was started by the numerous coins put into Mrs Bramwell’s [Florence Booth’s] hands before she left the tea-table’. This warm welcome appeared to bear out the claim that the plan had been devised to meet the demand that was often expressed in letters from ‘old girls’ for ‘an outlet for their love and thankfulness’ and their ‘desire to help one another’.

In the following months, the scheme – as yet without a name – was regularly promoted in The Deliverer (the monthly magazine of the Women’s Rescue Work). An officer, Mrs Colonel Barker, was specially appointed to correspond with the 2,400 rescued women who, it was believed, could afford to contribute to the fund, and tales of some contributors were printed in The Deliverer to encourage others.

However, in October 1892, a little over a year after the scheme was launched, it was announced that the sum raised from ‘gifts […] contributed weekly by dear girls who have passed through our Homes’ had reached £53 12s 1d. This fell considerably short of the anticipated £500 a year that would have been needed to start and maintain a home. The plan may have overestimated what the women could afford, or enthusiasm may have been tempered by the scheme being framed as a way to ‘repay […] the toil, the care, the love and the expense […] expended upon them’. The sense of financial and emotional obligation could have acted as a disincentive to continue contributing once the formal debt was considered repaid.

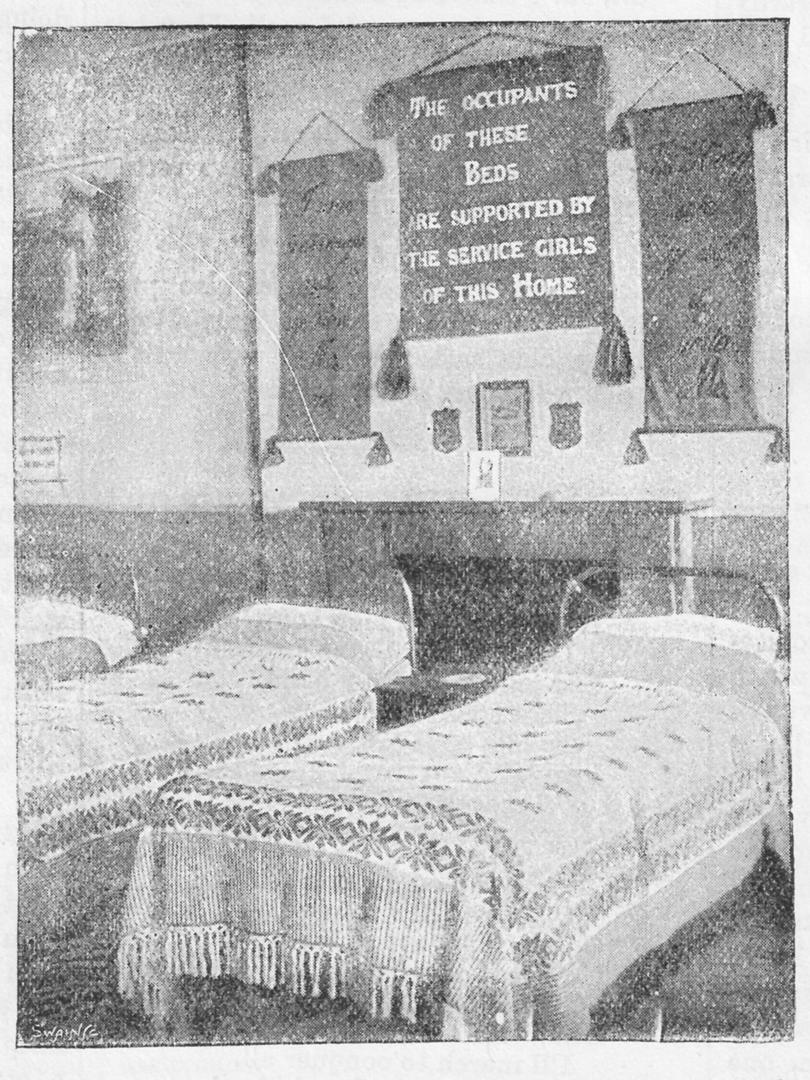

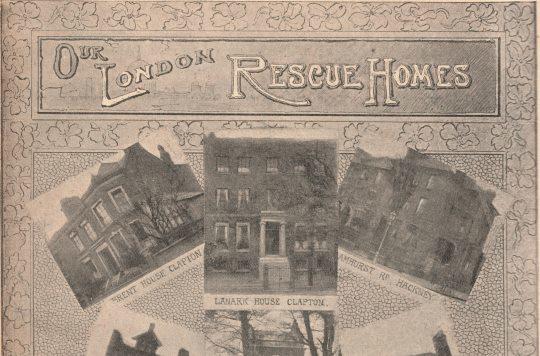

Whatever the reasons for the slow start, the amount raised was nonetheless celebrated as a triumph and so, in order to put it to good use, the purpose of the scheme was quietly changed. Instead of funding a new home, the contributions were used to fund beds in existing homes. These were known as ‘service girls’ beds’ after the women working in domestic service who funded them. The photograph below shows the first beds at Clapton Square rescue home that were supported by the scheme.

It took until 1894 before a name was settled upon for the scheme: the Out-of-Love Fund. By that time the fund was reportedly receiving contributions in excess of £100 a year, and a Roll of Honour had been set up to recognize and reward those who had accomplished the goal of ‘[wiping] off their debt to the friends of the Rescue Work, by refunding all that has been spent upon them over and above what they had been able to earn while in the Homes.’

It is interesting that the announcement of a name so suggestive of spontaneous generosity coincided with the most explicit indication to date that a real financial debt was considered owing. In 1900, it was reported that the amount expected to be repaid was £3 (equivalent to roughly nine days’ wages for a skilled tradesman). The choice of name proved apt, however, as the love, generosity and desire of the women to help others like them became ever more apparent.

As the years went by The Deliverer routinely gave reports of women who had repaid the monetary cost of their rescue but continued to contribute ‘quite voluntarily, towards the “Out-of-Love” beds’, money ‘that out of small earnings […] is gladly and spontaneously given’.

Most rescue homes began to host regular Out-of-Love teas to nurture the familial bond between residents old and new, provide ongoing support to past residents, and encourage them in their giving. Moreover, these teas were opportunities for past residents to deservedly take pleasure in seeing the fruits of their generosity: ‘whenever they visit the Home they “must have a peep” at their beds before leaving.’

The Out-of-Love scheme lasted well into the twentieth century. In 1920, the original ambition of establishing a home funded by the Out-of-Love donations was revived by Florence Booth’s successor as leader of the Women's Social Work, Commissioner Adelaide Cox. She wrote:

The ‘Out-of-Love’ and Thanksgiving contributions of the women who have passed through our Homes and are now doing well in various positions in life, amount to rather more than a thousand pounds a year, and I feel that it would be such a testimony to the labour of the thirty-five years of our life as a Department if we could establish a Home to be jointly supported by the earnings of the workroom and this contribution.’

Her intention was to name this new home Florence Booth House in recognition of the work of her predecessor. However, this plan appears to have faded away again. Although a Florence Booth House was established in Dundee almost a decade later in 1929, there is no evidence it was the intended Out-of-Love home.

Rather surprisingly, in 1920 the repayment amount that merited entry to the Roll of Honour and the gift of a bible had not grown since 1900 – it was still set at £3, which makes the reported growth in income to over £1000 a year an even more remarkable testimony of these women’s generosity. In one Salvation Army women’s hostel the Out-of-Love tradition carried on until at least the mid-1960s.

At Hope Town in the east end of London, Out-of-Love teas were still being held annually in 1965, with the ‘Leaguers’ (‘women who had during the past ten years been helped at Hope Town and since become Salvationists’) contributing £64 that year. This longevity is testament to the enduring importance of what recent scholarship has shown to be one of The Salvation Army’s late-nineteenth-century innovations: ‘establishing mass, small-donor markets in less affluent contexts’.

In their book, The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, Sarah Roddy, Julie-Marie Strange and Bertrand Taithe name the Out-of-Love Fund among a suite of Salvation Army initiatives that sought to offer meaningful opportunities for giving (or giving back) to anyone regardless of their means.

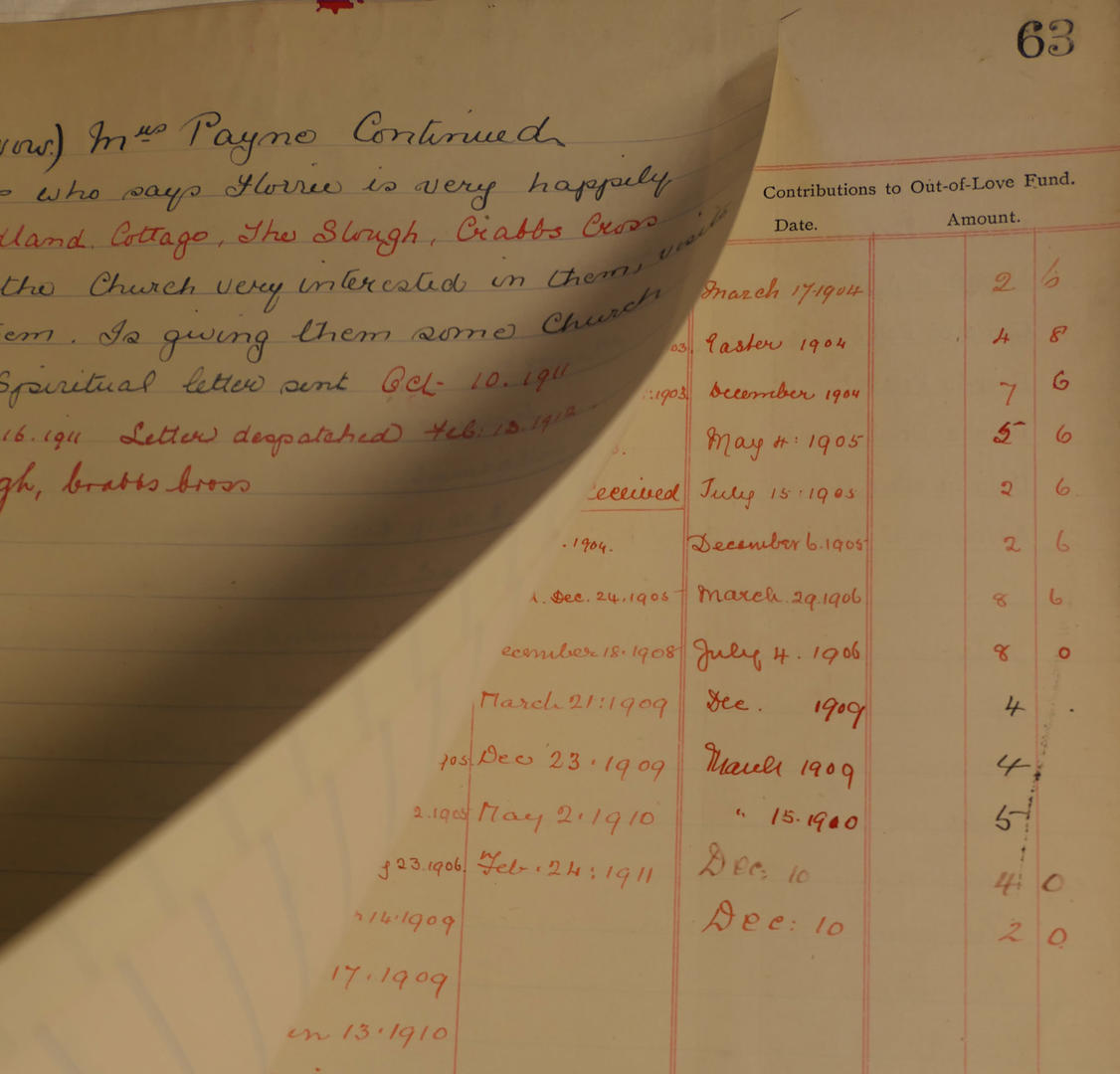

What makes the Out-of-Love Fund quite unique among these is the amount of detail that has survived about some of the individual donors, their contributions and their long-term relationship with The Salvation Army. In our archives we hold ‘History Books’ from several of The Salvation Army’s late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century homes for women (you can read more about these in some of our other blog posts linked below).

As well as a statement describing each woman who applied for help, the circumstances that led her to apply and her conduct while in the home, some of these books also include a second page dedicated to the woman’s career after leaving the home. This page was used to document all subsequent contact with the woman including letters sent and received, her attendance at tea meetings, and even chance encounters or hearsay reports of her. The page also includes a record of her Out-of-Love contributions.

Because these records were written and kept by The Salvation Army’s rescue officers they do not offer direct access to the voices of the women who contributed to the Out-of-Love Fund, their private feelings about the predicament that led them to seek help, their experience of being in the rescue home, or their reasons for contributing. But they do offer opportunities to glimpse and infer these things by reading between the lines or against the grain of their recorded statements and actions.

And the fact that these contributions were recorded in such detail is testament to their multi-layered significance to Salvation Army rescue officers: the small contributions cumulatively held financial importance, but they also held symbolic importance as a measure of the success of their efforts to materially help and spiritually redeem. Most importantly, however, these records bear witness to the generosity of successive generations of ordinary women, women of modest means, and their desire to help one another.

Ruth

December 2021

Other related posts from our blog

Guest blog: Location, Location, Location

This month we have a guest blog from our Birkbeck University intern, Imogen, exploring the who, what and why of The Salvation Army's east end Knitting Home...

A closer look at The Salvation Army's London Rescue Homes

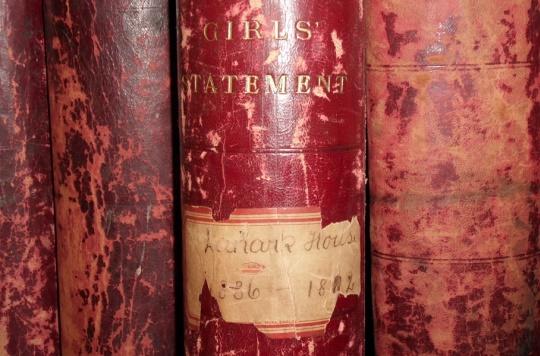

The Girls’ Statement Book VII is one of more than 120 volumes containing details of women and girls who passed through Salvation Army rescue homes...

First World War Babies

Between 1897 and 1972, women seeking admission to Salvation Army homes in the United Kingdom were interviewed at The Salvation Army’s Women’s Social Work (WSW) headquarters in London...

A lesson in judging books by their covers

Looking at the above picture you’d be forgiven for thinking that the volume in the centre would be easy to describe in our archive catalogue...